Jasco Confocal Raman Imaging Microscope : Principles, process, and Applications

Discovery of Raman

In 1922, Indian physicist C. V. Raman published his

work on the "Molecular Diffraction of Light", the first of a series

of investigations with his collaborators that ultimately led to his discovery

of the radiation effect that bears his name. In physics, Raman scattering or

the Raman effects the inelastic scattering of photons by matter, meaning that

there is both an exchange of energy and a change in the light's direction.

Experiment

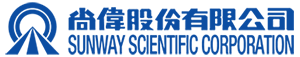

Figure 1: Raman experiment schematic diagram 1. The light source is not illuminated on Sample.

Light source: Sunlight passes through the lens and enters the filter 1 in parallel.

Filter 1: Filter out a specific wavelength and block other wavelength.

Filter 2: Completely block the wavelength filtered by Filter 1 and allow any other wavelength to pass.

Sample: An object has Raman scattering.

Observer: An observer.

Explanation: Sunlight is filtered out a specific wavelength through Filter 1, then completely blocked by Filter 2, so that Observer cannot see any light.

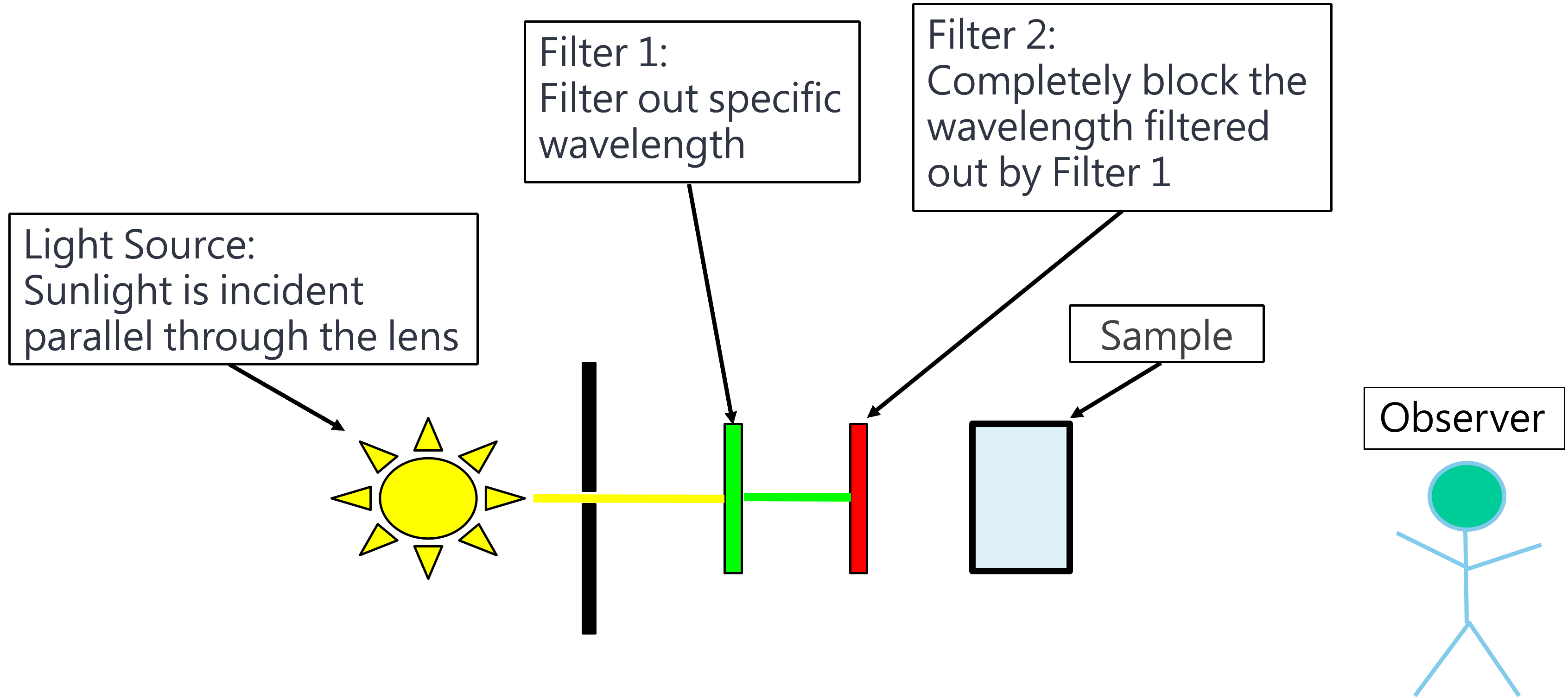

Figure 2: Raman experiment schematic diagram 1. The light source is illuminated on Sample, and then Sample releases Raman scattering.

Explanation: When sunlight is filtered a specific wavelength through Filter 1 to Sample, the observer still sees some light after Filter 2. It means that Sample scattering some wavelength which is different from the light filtered through Filter 1. This scattering wavelength is called Raman scattering.

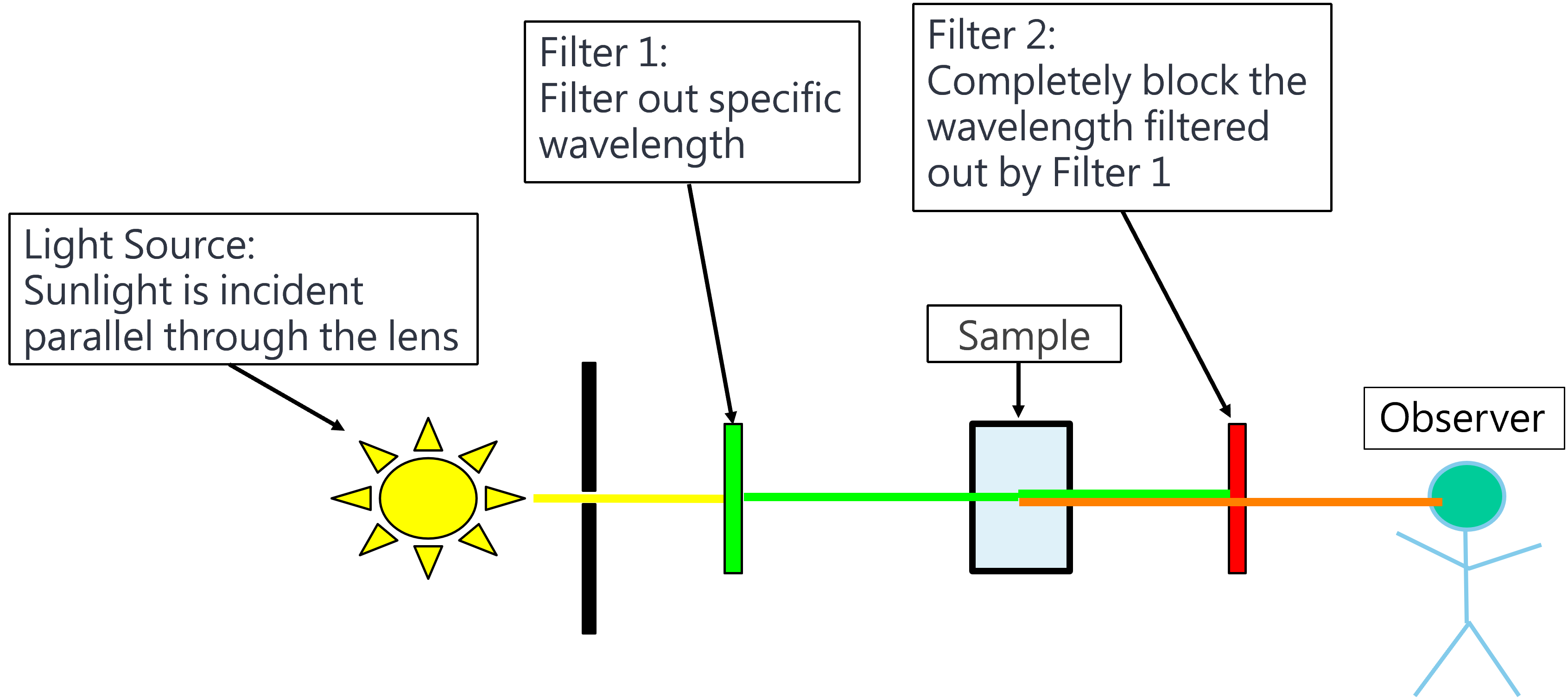

Elastic and inelastic collisions in photons

Light has a certain probability of being scattered by a material. When photons are scattered, most of them are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering), such that the scattered photons have the same energy (frequency, wavelength, and color) as the incident photons.

An even smaller fraction of photons is scattered inelastically, with the scattered photons having an energy different from those of the incident photons—these are Raman scattered photons.

In thermodynamic equilibrium, the lower state (Stokes transitions) will be more populated than the upper state (anti-Stokes transitions). Therefore, Stokes scattering peaks are stronger than anti-Stokes scattering peaks.

Figure 3: Energy-level diagram showing the states involved in Raman spectra.

Applications

Raman spectroscopy is used in chemistry to identify molecules and study chemical bonding and intramolecular bonds. Because vibrational frequencies are specific to a molecule's chemical bonds and symmetry (the fingerprint region of organic molecules is in the wavenumber range 500–1,500 cm−1), Raman provides a fingerprint to identify molecules. For instance, Raman and IR spectra were used to determine the vibrational frequencies of SiO, Si2O2, and Si3O3 on the base of normal coordinate analyses. Raman is also used to study the addition of a substrate to an enzyme. In solid-state physics, Raman spectroscopy is used to characterize materials, measure temperature, and find the crystallographic orientation of a sample.

Polarization dependence of Raman scattering

Raman scattering is polarization sensitive and can provide detailed information on symmetry of Raman active modes. Polarization effects on Raman spectra reveal information on the orientation of molecules in single crystals and anisotropic materials, e.g. strained plastic sheets, as well as the symmetry of vibrational modes.

Raman microscope

The Raman microscope begins with a standard optical microscope, and adds an excitation laser, laser rejection filters, a spectrometer or monochromator, and an optical sensitive detector such as a charge-coupled device (CCD), or photomultiplier tube, (PMT). Traditionally Raman microscopy was used to measure the Raman spectrum of a point on a sample, more recently the technique has been extended to implement Raman spectroscopy for direct chemical imaging over the whole field of view on a 3D sample.

如果您有任何其他問題,歡迎洽詢尚偉股份有限公司。

公司電話:02-27718337

公司傳真:02-27414646

公司信箱:mrkt@sun-way.com.tw